FROM THE FARM REPORT: THE ICE AGE AND SOILS IN THE LAKE CHAMPLAIN BASIN

- Laura Klaiber

- Sep 19, 2025

- 3 min read

Over the past six years I’ve written extensively in these pages about the agronomic and environmental impacts of tile drainage, as did Eric Young before me, and Ev Thomas before him. With so much ink spilled on the topic, I hope you’ll permit me a quick trip back into the past to help explain its importance to the region, and why it was adopted locally long before it achieved the widespread popularity it now boasts throughout our farming communities.

We have to go back three million years ago to the start of the most recent Ice Age, which subsequently reshaped the landscape as glaciers formed, grew and advanced southward during cooler periods, then shrunk and withdrew northward during warmer spells. As the glaciers cycled through this process of advance and retreat, they carved up the earth’s surface, eroding and transporting bedrock and soils substantial distances, and ultimately played a major role in the incredible variability of soil types and textures that are in the region.

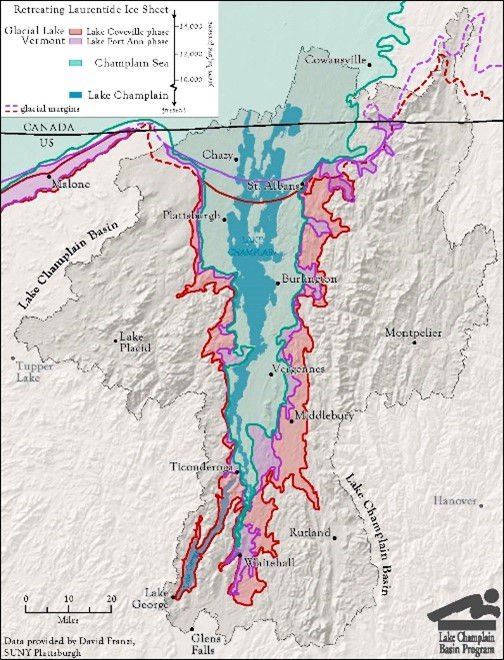

While movement of the glaciers helps explain many of the patterns and locations of our very rocky and coarser-textured soils, it’s the disappearance of the glaciers beginning about 15,000 years ago that really explains our abundance of fine-textured, poorly drained soils in much of the region’s cropland. If you take a look at map A, the dark grey region shows the footprint of the Lake Champlain watershed (all of the land area that ultimately drains into the lake). The very central, dark blue section of the map shows the location of Lake Champlain today. However, for several thousand years after the glaciers melted, a much larger area of the landscape was inundated with water.

During the first post-glacier phase, we had two phases of Glacial Lake Vermont, represented by the red and purple regions on Map A. This was a freshwater lake as we are today, but covering much more area east to west than the current lake. Surprisingly, given our apparent landlocked location, Glacial Lake Vermont was ultimately replaced by the Champlain Sea, depicted in light blue on the map. The Champlain Sea formed because the weight of the glaciers on the earth’s surface was so great that it compressed the entire region to the point where it was below sea level. Once the glaciers and subsequent meltwaters receded, waters from the Atlantic Ocean just followed gravity and flowed downhill into the basin and the formation of an inland sea!

Now the important thing to realize is that the water has a major impact on the movement of our three size classes of soil – sand, silt, and clay. Most of us have spent time on a beach, whether it’s a lake or ocean, and felt the sand beneath our toes. And what do we feel? Lots of uniform sand particles, which we can see everywhere we look, but nary a silt or clay particle anywhere! But walk out 20, 50, 100 ft into the water and now there is likely a very different feeling between your toes; probably much softer and squishier! Because sand particles are large and heavy enough, they never end up out past the shorelines because the water speed and its ability to carry things with it, drops dramatically. Conversely, we only see silt and clay particles in the main water body because they are only able to drop out of the water in the quieter waters away from the coastlines.

With all of that in mind, now take a look at Map B, which also shows the Lake Champlain Watershed shaded in grey and the current area of Lake Champlain in blue. The red and yellow shaded areas are poorly drained clay soils, and while the title of the map gives it away, if we look at the two maps together it becomes clear that the amount and geographic distribution of our heavy clay soils are directly tied to landscape and climate changes occurring 10,000-15,000 years go.

Hopefully you’ve stuck with me this far and if so, be sure to check back next month when I’ll talk a bit more about the history of tile drainage and share some pictures that probably do a much better job conveying the challenge that farming these heavy clay soils to the uninitiated!

— Laura Klaiber